Internationalizing a React Application using Polyglot

Internationalizing an application is always simple at first glance. It only consists on

applying a translate function on strings to be translated, right?. This function is generally

a mapping function, linking an input key (the string to be translated) to the returned

translated string.

Sounds simple? What about handling plural forms? It doesn’t consist in just adding an s

at the end of the word (see mouse and mice for instance). So it also needs to

handle singular and plural form. And, what about some Slavic languages where there are several plural forms?

For instance, in Russian, there is the singular form for a single element, the dual form for

between 2 and 4 elements, and the plural form for 5 or more elements.

It becomes quite complex, and we just talked about strings, not even date or currency formats. Fortunately, we can rely on some i18n libraries, whose most famous in React ecosystem are probably node-polyglot and react-i18next.

I won’t cover the differences between these two different libraries, as I don’t know enough react-i18next. Indeed, Polyglot was already present on the project we maintain, and does perfectly the job. Why switching to another lib if everything works well and is simple to develop? Just be pragmatic!

Discovering Polyglot

First, we need to grab Polyglot dependency:

npm install node-polyglot

Be careful: the Polyglot we retrieve here is the Airbnb one, called node-polyglot. There is also a polyglot package, but it is not the one covered by this post.

A First Translation using Polyglot

Reading the official documentation, we can achieve our first translation very easily, using a code similar to:

import Polyglot from 'node-polyglot';

const locale = 'fr';

const phrases = {

'actions.fullscreen': 'Voir en plein écran',

};

const polyglot = new Polyglot({ locale, phrases });

console.log(polyglot.t('actions.fullscreen');

// Voir en plein écran

We instantiate a Polyglot instance passing it two properties:

- locale: current locale, used only for pluralizations,

- phrases: a list of translations.

Then, translating a string is as simple as calling the t function and passing it the string to be translated.

String Interpolation

Let’s imagine we need to display a customized welcome message to our users. We would need username variable in our string. That would be especially useful to handle punctuation properly. Indeed, assuming we want to display Welcome Jonathan! once logged in, we may use a code like:

const phrases = {

'home.welcome': 'Welcome',

};

const polyglot = new Polyglot({ locale, phrases });

const login = 'Jonathan';

// Welcome Jonathan!

console.log(polyglot.t('home.welcome') + login + '!');

It works for English. But not in French, where there is always a space before exclamation points. So, we need to embed the login into our translation. Polyglot supports string interpolation, easing our job:

const phrases = {

'home.welcome': 'Welcome %{login}!',

};

const polyglot = new Polyglot({ locale, phrases });

const login = 'Jonathan';

// Welcome Jonathan!

console.log(polyglot.t('home.welcome', { login }));

Polyglot replaces all instances of %{variableName} by variableName value, allowing to embed

our punctuation directly into our translated strings. In French, it would have been Bienvenue %{login} !.

Handling plural forms

As explained above, handling plural forms is not as trivial as it may sound. Fortunately, Polyglot handles it natively:

const phrases = {

'numberChildren': '%{smart_count} child |||| %{smart_count} children',

};

const polyglot = new Polyglot({ locale: 'fr', phrases });

// 1 child

console.log(polyglot.t('numberChildren', { smart_count: 1 }));

// 3 children

console.log(polyglot.t('numberChildren', { smart_count: 3 }));

Note the |||| symbol which is the plural form separator. As Polyglot is configured in French (via

the locale attribute), it splits the translation string on this symbol, and considers the first part as the singular form and the last one as the plural form. We can, if we need to support Russian for instance, have several |||| in the same translated string.

Number of items is retrieved from the special smart_count variable.

So, that was the getting started of Polyglot. Yet, how do we use it in a real-world application, where you need it in several files?

Using Polyglot in a Real World Application

There is generally a huge gap between the straightforward getting started tutorial and its integration into a real-world application.

Polyglot is not an exception to the rule. Just following the tutorial, how can we use it in all our React components without instantiating it several times? The quick and dirty solution would be to declare it globally via a global.translate property. Yet, not fully satisfying, as we are going inevitably to face some troubles using global variables.

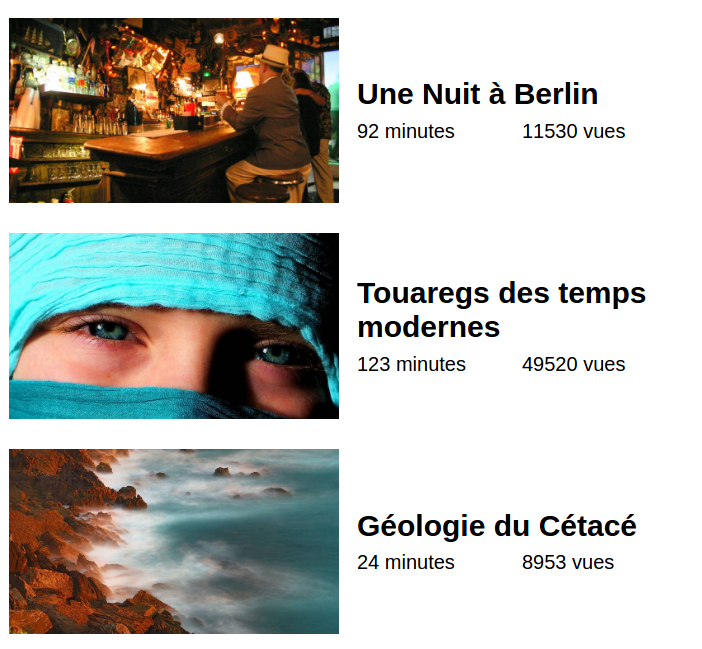

Explaining how to implement Polyglot on a real-world application requires a real-world application. I bootstrapped a really basic video list application. You can grab the whole source code on GitHub, each commit bringing improvement compared to the previous one.

Our sample application contains three components: a <VideoList /> displaying a list of <Video />, each one having a <Metas /> component (for duration and number of views). Code is basic React and I’ll assume you have a basic knowledge of this awesome lib. That’s why I won’t cover the setup part and focus on the internationalization part.

The Naive Solution

The first naive solution would be to declare a Polyglot instance once, in our top level script, and then passing it manually via props to all our children. For instance, we may write the following code:

import React from 'react';

import ReactDOM from 'react-dom';

import Polyglot from 'node-polyglot';

import videos from './data';

import messages from './messages';

import VideoList from './VideoList';

const locale = window.localStorage.getItem('locale') || 'fr';

const polyglot = new Polyglot({

locale,

phrases: messages[locale],

});

const translate = polyglot.t.bind(polyglot);

ReactDOM.render(

<VideoList videos={videos} translate={translate} />,

document.getElementById('root')

);

export const VideoList = ({ translate, videos }) => (

<div className="videos-list">

{videos.map(video => (

<Video

key={video.title}

video={video}

translate={translate}

/>

))}

</div>

);

export const Video = ({ video, translate }) => (

<div className="video">

<img

src={video.picture}

alt={video.title}

/>

<div className="infos">

<h2 className="title">{video.title}</h2>

<Metas

metas={video.metas}

translate={translate}

/>

</div>

</div>

);

export const Metas = ({ metas, translate }) => (

<div className="video-metas">

<div className="duration">

{translate('minutes', { smart_count: metas.duration })}

</div>

<div className="views">

{translate('views', { smart_count: metas.views })}

</div>

</div>

);

This naive implementation works perfectly, but is incredibly cumbersome and thus error-prone, due to the numerous translate prop transfers . This basic sample handles only three levels of components. What about a more complex application with sometimes a dozen of depth levels? We need a better solution. Especially as only the <Metas /> component needs the translate prop.

What About Using Context?

To Use or Not To Use Context?

Fortunately, React provides a solution. Reading the official documentation:

In some cases, you want to pass data through the component tree without having to pass the props down manually at every level. You can do this directly in React with the powerful “context” API.

That’s exactly what we need. Yet, a few lines later, we can read, still on the same page:

If you want your application to be stable, don’t use context. It is an experimental API and it is likely to break in future releases of React.

Not really encouraging. So, it perfectly fits our need, but is not recommended. What should we do? When facing such questions, the best solution is to refer to the developer collective intelligence. Dan Abramov, a high-skilled developer you need to follow if you are interested in the React ecosystem, shared a code snippet on Twitter:

function shouldIUseReactContextFeature() {

if (amIALibraryAuthor() && doINeedToPassSomethingDownDeeply()) {

// A custom <Option> component might want to talk to its <Select>.

// This is OK but note that context is experimental API and doesn't update

// correctly in some cases so you might want to roll your own subscriptions.

return amIFineWith(API_CHANGES && BUGGY_UPDATES);

}

if (myUseCase === 'theming' || myUseCase === 'localization') {

// In apps, context can be used for "global" variables that rarely change.

// If you insist on using it, provide a higher order component.

// This way when we change the API, you will only need to update one place.

return iPromiseToWriteHOCInsteadOfUsingItDirectly();

}

if (libraryAsksMeToUseContext()) {

// Ask them to provide a higher order component!

throw new Error('File an issue with this library.');

}

// Good luck.

return yolo();

}

So, using context for localization is fine, but only with a Higher Order Component (HOC). Let’s focus on how to use context for now.

Using context consists in creating a Provider, which should fulfill three different requirements:

- Declare data structure of context passed data,

- Fill context data,

- Render

childrencomponents.

Writing our First Provider

In our case, we are going to pass the translate function to the context. But also the locale as a string. Indeed, we may need it if we want to localize dates using moment for instance. So, let’s declare our context new data types:

import { Children, Component, PropTypes } from 'react';

class I18nProvider extends Component {

};

I18nProvider.childContextTypes = {

locale: PropTypes.string.isRequired,

translate: PropTypes.func.isRequired,

};

export default I18nProvider;

Now, we need to fill the context new attributes, via the getChildContext method. That’s where we need to instantiate Polyglot:

// [...]

class I18nProvider extends Component {

getChildContext() {

const { locale } = this.props;

const polyglot = new Polyglot({

locale,

phrases: messages[locale],

});

const translate = polyglot.t.bind(polyglot);

return { locale, translate };

};

};

// [...]

We use the locale prop passed to the Provider instead of retrieving it directly via the local storage. Indeed, this logic should not be embedded in such a “dumb” provider.

We can now use our Provider in our application. So, let’s change our index.js render script:

const locale = window.localStorage.getItem('locale') || 'fr';

ReactDOM.render(

<I18nProvider locale={locale}>

<VideoList videos={videos} />

</I18nProvider>,

document.getElementById('root')

);

We wrapped our <VideoList /> component in our <I18nProvider />, adding it a locale property. That’s the only change we need to bring to our application. All the instanciation logic is decoupled in the provider, keeping our code really readable.

Yet, our <I18nProvider /> has no render method yet. It would then display nothing. In this case, this method should just proxy the display of component child.

import { Children } from 'react';

// [...]

class I18nProvider extends Component {

render() {

return Children.only(this.props.children);

}

};

// [...]

But We Promised Dan to Write a HOC…

If we remember correctly Dan’s previous tweet, we promised him to write a Higher Order Component (aka HOC). But what is it?

A higher-order component (HOC) is a function that takes a component and returns a new component.

In our case, HOC is useful as it allows to map our base component with our new context attributes. It would return a new component passing translate and locale as props. Such a HOC code would be:

import React, { PropTypes } from 'react';

export const translate = (BaseComponent) => {

const TranslatedComponent = (props, context) => (

<BaseComponent

translate={context.translate}

locale={context.locale}

{...props}

/>

);

TranslatedComponent.contextTypes = {

translate: PropTypes.func.isRequired,

locale: PropTypes.string.isRequired,

};

return TranslatedComponent;

};

export default translate;

We map our component to the context thanks to the contextTypes property. It takes the same data structure as our I18nProvider.childContextTypes. Then, we can retrieve it thanks to the second argument of our functional component.

Now we get our HOC, we just need to remove all former translate props from our components, and just call our translate function on our <Metas /> component:

import translate from './translate';

export const Metas = ({ metas, translate }) => (

// [...]

);

export default translate(Metas);

Our internationalization is now quite straightforward, just requiring a function call to our translate component to access Polyglot. And we also learned how to create a Provider. Level up!

Final code is available on GitHub as the penultimate commit. HEAD of the repository uses recompose to simplify code slightly.